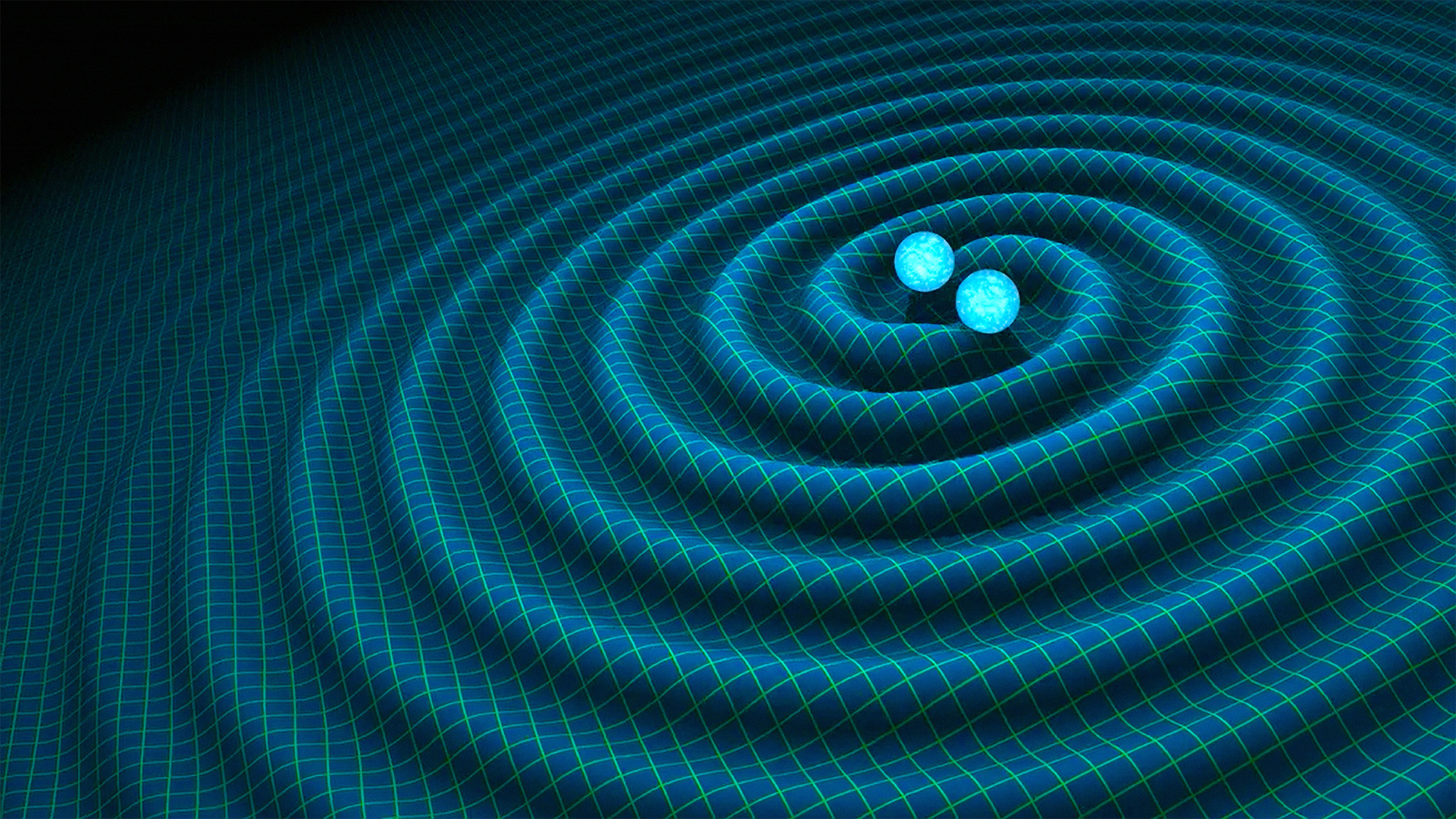

Gravitational waves

Why am I interested?

To begin with, I did my Ph.D. in gravitational waves (GW). I was often asked how did I decide to study black holes and GWs, and my answer is: it is simple. In my mind, black holes and GWs are highly idealized objects. Think about a black hole binaries, the model we use to describe the GW it generates has 15 numbers: 2 masses, 6 spins, 4 sky angles, time and phase of coalescence, and distance. And how does the data look like? A time series of the strain and that's it. On top of that, our theory of gravity is incredibly clean and well verified. Claiming you found something wrong in general relativity usually put you in the last session of the last day in APS, or a special table with similar minded people in any other conference.

Yet, problems in GW are quite challenging. Our data is extremely noisy (Veritasium has a great video on this), the statistics we have is small, and the accuracy requirement on our model is brutal because of how well we know GR. For example, the parameter estimation (PE) problem is quite simply defined: given a time series and a model, establish the parameters of the source. In principle, one can just throw a big enough machine and MCMC at it and get the answer. However, the challenge is to do it in a reasonable time and with a reasonable accuracy. GW PE has all sort of technical challenges to it, multimodality, (somewhat) high dimensionality, local correlation, etc. Working on GWs problem is kind of like pushing a boulder uphill like Sisyphus: here is your boulder, now put it on top of the hill. Very well defined and simple, but boy it is hard.

This makes the problem straightforward and difficult at the same time, and it makes GW a great test bench for many statistical and computational methods.

What do I work on?

I am mostly interested in the tool development and the data analysis side of GWs. Here is a list of research problems I am working on:

Accelerated parameter estimation

One of the most important task in GW data analysis is parameter estimation: given a time series of the strain and a model of the signal, guess what are the parameters corresponds to the observed event. This is often done by some sort of sampling such as nested sampling or MCMC, which can be quite expensive, ranging from hundreds to thousands of CPU hours per event.

There has been different attempts to speed up parameter estimation, either through more modern engineering but sticking with traditional sampling method, or completely new deep learning-based method such as simulation-based inference. On this topic, I developed an open-source package jim to provide the community a fast code to estimate parameters. We used a bag of tricks, including some machine learning, some GPUs, smart math related to gravitational wave, and more. The idea behind jim is it should be extensible by the user, run fast, and reasonably robust (and if it start failing, at least it should tell you so). Jim is still in active development, if you are interested or have feedbacks, please feel free to open an issue! We welcome any suggestions and contributions.

Modern waveform model

Numerical relativity simulations provide the most accurate waveform model. However, they usually takes hours or even weeks to simulate for one set of source parameters. PE often requires at least 10^5 waveform evaluation to get a good estimate of the posterior, so using NR waveform directly is not feasible. Because of this, many groups have contributed to building approximation to NR waveform, such as IMRPhenom, SEOBNR, and the surrogate model. Since these approximation families have different assumptions going into their model, they have different systematics and tradeoffs compared to NR as a baseline.

Waveform models are critical to any GW studies ranging from search, parameter estimation to interpretation, so making sure they are high performance and suitable for downstream tasks is what I am passion about. More specifically, I am interested making "modern" waveforms, which should include features such as automatically differentiable, compatible with accelerators, and be able to account for calibration uncertainties. I am a developer involved in an open-source package ripple. Once again if you have suggestions or want to contribute, please get in touch!

Numerical relativity

Having incredibly accurate numerical relativity (NR) simulations and waveform catalog is one of the reason why the community can build surrogate waveform models such IMRPhenom, SEOB, and the surrogate, which in turns give our detector more sensitivity through match filtering. In the coming decade (2030-2040), next generation detectors are going to be built. They are sensitive enough which the accuracy of NR simulation could be a limiting factor. One of the question is how can we improve the existing model, in turns requiring us to simulate NR signal in a more precise fashion. There are multiple famous group such as caltech and cornell working on this, I am by no mean an expert in simulation, as my education background is not based on works related to simulations. Yet, I am very curious about what modern computing paradigm and deep learning can do for numerical relativity. For me, it is not so important that I make the best NR simulations or gain some new insights to a particular system, there are more qualified people than me to do that. I am more interested in designing algorithms and making code that might contribute to building the next generation NR simulations. For example, when the mass ratio of the system is going to more and more extreme, there are multiple time and length scales one has to resolve. This is usually done either by domain decomposition or adaptive mesh refinement. Whenever there is such hierarchy of scales, there is some interpolation involved in between different scales. Can machine learning learning helps? Another example is eccentric system. Ideally we would want to simulate the entire signal with the prescription from NR, but then we are spending a lot of time in parts which the two objects are far apart and interacting weakly. Can we learn to approximate that part on-the-fly.